“Children of a culture born in a water-rich environment, we have never really learned how important water is to us. We understand it, but we do not respect it.”

~ William Ashworth

Introduction

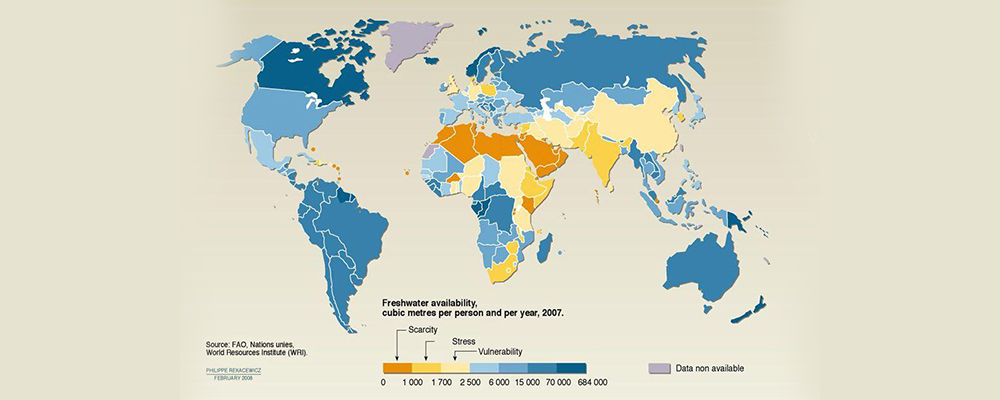

Women are always more vulnerable to most of the hazards and crises. The importance of women’s roles and gender relations in water has shifted over the last few decades. One-third of the world’s population is currently affected by water scarcity, either physically or economically. The majority of the world’s 1.2 billion poor people, two-thirds of whom are women, live in countries where access to safe and clean water for economic and domestic purposes is restricted (IFAD 2001). By the mid-1970s, academics, practitioners, and activists working in the area of economic growth had understood that development and modernization had different impacts on men and women. Rather than being a rising tide that lifted all boats, the intended and unintended consequences of modernization were bypassing many women and even harming others. Overall, the process of economic development was radically changing women’s roles in the home and society at large.

Gendered Impact

According to a study conducted by the International Water and Sanitation Centre (IRC) of community water and sanitation projects in 88 communities across 15 countries, projects planned and run with full female involvement are more sustainable and successful than those that do not. This backs up a World Bank report that showed that women’s participation was closely linked to the success of water and sanitation projects. Women’s interests and natural resource management and conservation, according to powerful gender-equity proponents, have a positive synergy.

About 1.1 billion people lack access to the minimum quantity of water needed for basic health and hygiene, and this number is almost certainly an underestimate. Throughout the developing world, the task of providing domestic water is a lies on women. Thus, the health consequences of lack of access to water and of transporting water daily, and the policy frameworks in which access can be improved, are of particular relevance to women and development. The minimum amount of water required for domestic use, which usually means drinking, cooking, washing utensils, and maintaining basic hygiene, can be described in a variety of ways.

The UNICEF/World Health Organization Joint Monitoring Program (JMP), the main source of national-level data on access, defines reasonable access as 20 liters of water per person per day from an improved source, no more than 1 km. distant from the dwelling. Current JMP estimates are that 85% of the population has access in Latin America and the Caribbean, 81% in Asia, and 62% in Africa. Globally, approximately 65% of the population without access to safe water lives in Asia and 28% in Africa. An estimated 842,000 people die each year from diarrhea due to unsafe drinking water and every minute a newborn dies from infection caused by lack of safe water. Even though these figures do not explicitly correlate to women’s access, they are fair substitutes since it is almost always women and children who are responsible for providing domestic water on a daily basis.

Urban and peri-urban areas in the developing world may have household connections or standpipe water within a short distance of the home. Women and children will not have to travel long distances in such situations, but standing in line takes time. According to survey data from across India, 21% of urban households said it took them 20 minutes or more to get to a water source, not including waiting time and the return journey. Waiting time of 1 to 2 hrs at water kiosks have been recorded in densely populated slums such as Kibera, Kenya, and slums in Dhaka, Bangladesh, may have a standpipe to person ratio of 1:500. As in rural areas, most of the task of fetching water and waiting in urban areas falls upon women and girls. Women and (usually) girl children fetch water in pots, buckets, or ideally more modern narrow-necked containers, which are carried either on the head or the hips. To meet their minimum needs, a family of five living within 1 km of an improved water supply will need 100 litres of water per day. Without the bottle, the water weighs 100 kg (220 pounds). Traditional clay pots are much heavier than plastic, which is the lightest material for carrying water. Women and children need to walk to the water source twice or thrice a day in these circumstances.

Health Concerns

Globally, more than 50% of poor women suffer malnutrition and iron deficiency, and thus it

should not be surprising that, especially during the dry season in rural India and Africa, 30% or more of a woman’s daily energy intake is may just in fetching water. When several trips are not possible, rural and peri-urban families make do with 10 liters or less per person per day, even if they live within 1 km. of an improved source, and thus have access. Carrying heavy loads over long periods causes cumulative damage to the spine, the neck muscles, and the lower back, leading to the early aging of the vertebral column. Symptoms such as persistent pain in the neck and knees are also possible. The burden of daily carrying is rarely covered in leading public health and epidemiological journals, as it falls outside of the conventional categories of water-benefit, water-washed, and water-related ailments.

Water supplies benefits may include a considerable reduction of water-related diseases. This will have the positive effects of less productive time lost to illness, better child attendance at school, less burden of care and women’s time-released for other activities. Women and men may have different local information about natural resources, as well as different concerns about the quality and quantity of water available, due to gendered labour divisions. Because of prevalent gender relations in their respective socio-economic contexts, women can often find it difficult to effectively perform such roles due to limited mobility, funds, and time. There are lots of causes of water scarcity such as overuse of water, pollution of water, global warming, groundwater pollution, governmental access, natural disaster etc.

The Islamic Solution

In today’s convenient world, we often don’t think twice before wasting water on unnecessary things such as washing our cars or just running the tap while waiting for the correct temperature. When we run a long bath, flush the toilet, excessively wash dishes, brush our teeth or spend extra time in the shower (just cozy, we feel like it) – it’s easy to overlook those who are in dire need of something we all too often throw away. Numerous ayahs in the Quran emphasise Allah’s (SWT) sending water down to Earth for the development and survival of life on the planet. “And waste not by excess, for Allah loves not the wasters.” (The Holy Qur’an -7:31).

The simple act of giving someone water is highly rewarded in Islam, so we can imagine what the reward would be for having access to a water source. This is known as sadaqah-e-jaariyah, and it will continue to benefit the givers even after they have passed away, as long as others continue to benefit from the given source of water. Another human being, an animal or even a plant may be a living thing; these are all the creations of God SWT.

The Holy Prophet (PBUH) once narrated: “The best form of charity is to give someone water.” Abdullah ibn Amr reported: The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, passed by Sa’d while he was performing ablution (wudhu). The Prophet said, “What is this excess?” Sa’d asked, “Is there excess with water in ablution (wudhu)?” The Prophet said, “Yes, even if you were on the banks of a flowing river.” (Sunan Ibn Mājah 425)

It’s convenient to take the natural resource of water for granted before we pause to think about it. Although we may not see or understand how much water we waste on a daily basis, it is still a vital component of life and something that many people around the world lack and pray for. We often learn from our academic textbooks how to utilize water. Most activists and scholars advocate for micro-level water resource management, in which women can play an important if they are provided with adequate information and training.

0 Comments