On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 landed on the moon’s surface, marking Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon. However, long before Armstrong had his historic moment, he uttered the iconic words: “That’s one small step for [a] man. One giant leap for mankind.” Several influential Muslim astronomers during the Golden Era of Muslim civilisation had already significantly contributed to studying our planet’s nearest celestial body.

The moon holds significant importance for Muslims because the Islamic calendar, known as the Hijri or Lunar calendar, is based on the moon’s cycles. Months begin with the sighting of the new moon, marking the start of each lunar month. A lunar cycle is approximately 29.5 days. This results in a lunar year of only 354 or 355 days, shorter than the solar year of 365 days. This makes the Hijri calendar 11 days shorter than the solar year. As a result, holidays such as Ramadan (the month of fasting) slowly cycle through the seasons. Each year, Ramadan begins about 11 days earlier than the previous year and falls on the same date only every 33 solar years.

Islamic months begin only when the crescent moon is sighted, so no one knows exactly when Ramadan will start until the crescent moon appears in the night sky. Predicting when the crescent moon would become visible was a special challenge for Muslim mathematical astronomers.

Claudius Ptolemy, a renowned second-century mathematician, astronomer, and geographer, made significant strides in understanding the movement of celestial bodies, particularly the moon. However, his focus primarily revolved around lunar phenomena like eclipses or the intersection of the sun’s path with that of the moon.

During the Middle Ages, Muslim scholars recognised the gap in predicting the appearance of the crescent moon. They realised that its movement about the horizon had to be studied to predict the sighting of the crescent moon. This challenge demanded a sophisticated mathematical approach known as spherical geometry, which deals with shapes on the surface of a sphere. Al-Kindi, a mathematician, philosopher and physicist, worked in Baghdad (the Capital of Iraq) during the ninth century and pioneered the development of spherical geometry. His groundbreaking contributions in this field became integral to his astronomical works, marking a significant advancement in the study of celestial phenomena.

Spherical geometry played a crucial role in understanding lunar movements and determining the Qibla, the direction of Mecca, which Muslims pray towards. Al-Biruni, a remarkable scholar, polymath, astronomer, mathematician and geographer of the 10th and 11th centuries, was instrumental in solving this navigational puzzle from any point on Earth’s surface. Often hailed as the Leonardo da Vinci of his era due to his wide-ranging interests, Al-Biruni’s contributions transcended boundaries.

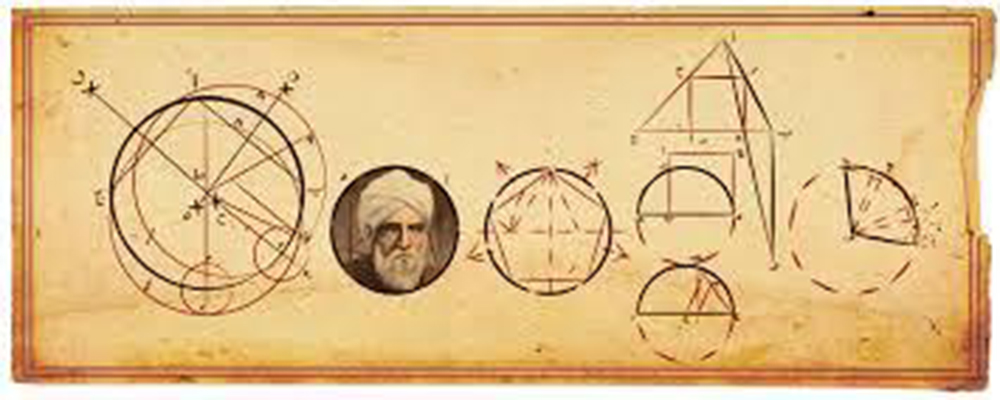

In his pursuit of astronomical knowledge, Al-Biruni meticulously documented celestial events. One such instance was his observation of the eclipse on May 24, 997, while he resided in Kath, present-day Uzbekistan. This cosmic phenomenon was also visible in Baghdad. Al-Biruni collaborated with his fellow astronomer, mathematician and geometrician, Abu al-Wafa’ al-Buzjani, who observed the eclipse from Baghdad. By comparing their respective timings of the eclipse, they could precisely calculate the difference in longitude between the two cities, showcasing the practical applications of their astronomical expertise.

In 975, Abu al-Wafa’ al-Buzjani made a significant discovery regarding the moon’s motion. He identified what is now known as the “moon’s variation,” marking the third inequality in the moon’s movement. This observation was a remarkable addition to the knowledge inherited from Ptolemy, who had previously recognised the first and second inequalities.

Abu al-Wafa al-Buzjani’s work illuminated a fascinating aspect of lunar dynamics: the moon’s varying speed in orbit. He noted that the moon moves fastest when it is either new or full and slows down during its cycle’s first and third quarters.

Interestingly, this discovery remained relatively obscure in Europe until approximately six centuries later when Tycho Brahe, a renowned Danish astronomer, rediscovered the moon’s variation around 1850. Abu al-Wafa al-Buzjani and Tycho Brahe significantly contributed to our understanding of celestial mechanics despite the time gap.

Moon watching and recording was a serious business. As it captivates us today, ancient civilisations were fascinated by the moon’s movements. Meticulously, logging the lunar patterns supported the idea that there is order in the heavens, too.

The Qur’an draws attention to this celestial order. It states, “And the moon, We have determined it by phases until it returns [appearing] like the old date stalk. It is not for the sun to overtake the moon, nor does the night outstrip the day. They all float, each in an orbit. ” (36:39-40)

And He is the One Who created the day and the night, the sun and the moon—each traveling in an orbit. (21:33)

And He has subjected for your benefit the day and the night, the sun and the moon. And the stars have been subjected by His command. Surely in this are signs for those who understand. (16:12)

Through these verses, the Qur’an conveys that behind these astronomical phenomena lies a coherent system that people are invited to explore. These verses also challenge people to acquire the required knowledge to explore a universe abundant with God’s wonders.

Today, as we gaze at the same moon that enraptured our ancestors, we must continue their legacy of inquiry and reverence. Whether through the lens of a telescope or the verses of scriptures, we must seek to unravel the mysteries of the cosmos and find solace in the eternal order that governs the heavens above.

Amazing ♥️

It’s incredible how our ancestors contributed to science. Thank you for this informative article. I’m eagerly anticipating more informative articles.

Shandar